W.E.B. Du Bois’ Final Days

In 1899, while writing “The Souls of Black Folks”, Du Bois’ infant son became ill and swiftly declined. As Du Bois wrote his treatise on the necessary esteem of black people in our society, he struggled with the grief and horror of watching his baby son die.

Du Bois and his wife had recently moved from the progressive Northeast to Atlanta, leaving a city where a black family had equal access to healthcare and relocating to a city where the family did not. It is often speculated that if the family had stayed in Philadelphia, the child would have likely received treatment for his diphtheria. The excruciating pain of his son’s dying process becomes a chapter in Du Bois’ Magnus Opus. Even more, Du Bois considers whether it is better for his black son to die young and innocent than to survive the brutality of America’s institutionalized racism.

“Well sped, my boy, before the world had dubbed your ambition insolence, had held your ideals unattainable and taught you to cringe and bow. Better far this nameless void that stops my life than a sea of sorrow for you.”

Du Bois’ contribution to civil rights grew over the course of his long life: his prolific writings on the necessity of equality, his part in founding the NAACP, and his plight that higher education for African Americans is the path to equality. But no writing touches my heart more than the chapter on his son’s death and the grief that followed.

Read it here: https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/family/dawn-mourning

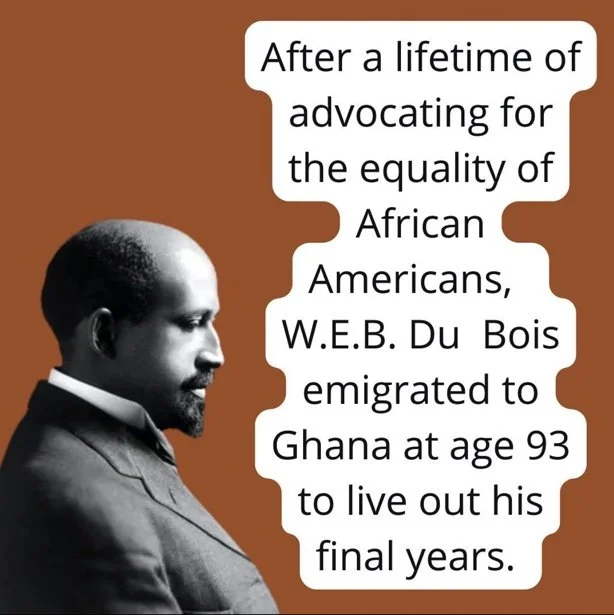

So imagine now this intellectual giant who dedicated his life to promoting equality between races. The first black man to ever graduate from Harvard, a brilliant mind furiously writing books, organizing, speaking, and leading, over the course of a 70-year career. To look back on his life and his legacy and his homeland and to finally say, “Enough.” To go to another country to seek his elusive equality in his final years. Heartbreaking and staggering at once.